The House Pod Gigantami ('Under the Giants'), where we had the Waterloo Dinner, is situated in Ujazdowskie Avenue 24, part of the Royal Way in Warsaw.

It was built between 1904 and 1907 by Władysław Marconi.

The original interior was preserved during WW II as it had the function of a

Nazi Officers' Club.

Blazej Zulawski arriving at Pod Gigantami in the Ferrari to be greeted by the Chairman

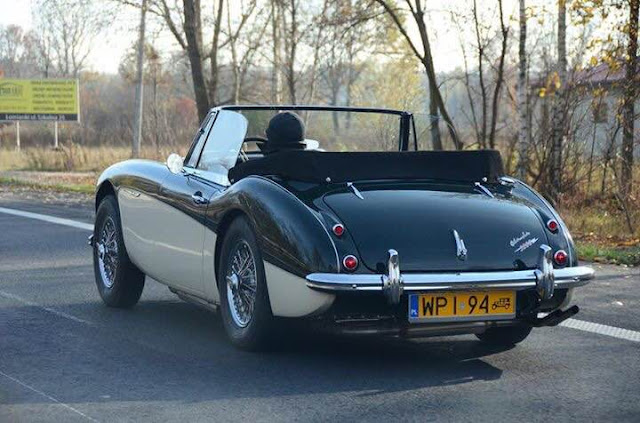

The Chairman's 1974 Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow I - SRH18723 (owned since 1987)

arriving at Pod Gigantami

The dinner was excellent and a convivial atmosphere was quickly established. Some new members of the club were welcomed.

Not quite this Waterloo Banquet held some time after the victory but we tried!

The Waterloo Banquet 1836 for 83 diners of the military persuasion by British artist

William Salter (1804-1875)

Rather later than anticipated I began my brief account of the complex preparations and Battle of Waterloo. I shall not go into any great detail here. Suffice to say I covered the main elements as they unfolded on the day.

A rare daguerreotype photograph of the Duke of Wellington at 75

The Duke of Wellington on 'Copenhagen' by

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830)

Portrait of Napoleon by

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825)

I find the contrast of these two portraits most instructive in terms of personality and style.

In order to accomplish this in an 'infotainment' manner (not to be overly serious following dinner) I used as a basis of my presentation excerpts from the television play Sharpe's Waterloo based on the novel by Bernard Cornwell.

I began with an account of the famous Duchess of Richmond's Ball.

The Duchess of Richmond's Ball by Robert Alexander Hillingford (1828-1904)

Battle of Ligny 16 June 1815 where Napoleon defeated Field Marshall Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher who used this windmill as his headquarters

British artist Ernest Crofts (1847-1911)

Intelligence arrives of the Blücher defeat at the Duchess of Richmond's Ball

I then covered the Battle of Quatre-Bras between Wellington's Anglo-Dutch army and the left wing of the Armée du Nord under Marshal Michael Ney. This battle was fought near the strategic crossroads of Quatre-Bras on 16 June 1815, two days before the Battle of Waterloo. Wellington only just managed to hold Napoleon here and retired to the village of Waterloo. Some months before the actual battle at Waterloo, Wellington had already planned to fight in this location and had had accurate maps of the terrain drawn up beforehand. This pre-planning gave him a distinct advantage.

The 28th Regiment at the Battle of Quatre Bras by the British painter Elizabeth Thompson (1846-1933). She is one of the few female painters to achieve fame through history painting.

Troop dispositions at Quatre-Bras and Ligny about 3.00 pm on June 18

(Waterloo by Tim Clayton, London 2014)

Battle of Waterloo: initial dispositions (Waterloo by Tim Clayton, London 2014)

Polish Lancer Unit attacking a British Square at Waterloo

Factually their participation is possibly somewhat fanciful. Polish soldiers contributed to the Battle of Waterloo

as part of the French Imperial Guard, particularly as lancers. While many

Poles returned to Polish territories after Napoleon's initial defeat, a unit of

around 325 men, including those under Colonel Golaszewski, continued fighting

in Napoleon's "Hundred Days" campaign and participated in the Battle

of Waterloo. These Polish cavalrymen, known for their bravery and skill,

were part of the prestigious Old Guard.

Waterloo at Close of Day by by Robert Alexander Hillingford (1828-1904)

* * * * * *

To the relief of some, our brilliant snapper Blazej Zulawski then gave us a tour of the highlights he photographed at the 2015 Villa d'Este Concours d'Elegance

Here are a few photographs of the assembled company at Pod Gigantami late on the night during his presentation

And a small selection of some hundreds of Blazej's photographs we were shown

(some identification captions to come)

Polish WW II General Sikorski's magnificent 1937 Rolls-Royce Phantom III with coachwork by Vanvooren of Paris

The Waterloo Dinner was a rather long but highly enjoyable evening with excellent food, wine and convivial CCC company.

CCC members present at this dinner:

Iain Batty

Ian Booth

Jacek Czeczot-Gawrak

Michael Moran

Michael Motz

Blazej Zulkawski

Guy Pinsent

Michael Wrobel

Jonathan Bowring

Mirek Staniszewski

Artur Gabor

Robert Windmill

Janusz Zawada

Paul Ayre, Paul Blackman, Neil Crook, Erik Hallgren, Edward Mier-Jędrzejowicz, Bill Flint, Michael Kenny sent their apologies.

Ladies present:

Basia Adam

Agata Zawada

Michael Moran (Chairman)